I wanted to read the book as I am interested in the author's father, Philip Toynbee and recently tracked down a copy of his book "Friends Apart" (published 1954) about Esmond Romilly and Jasper Ridley.

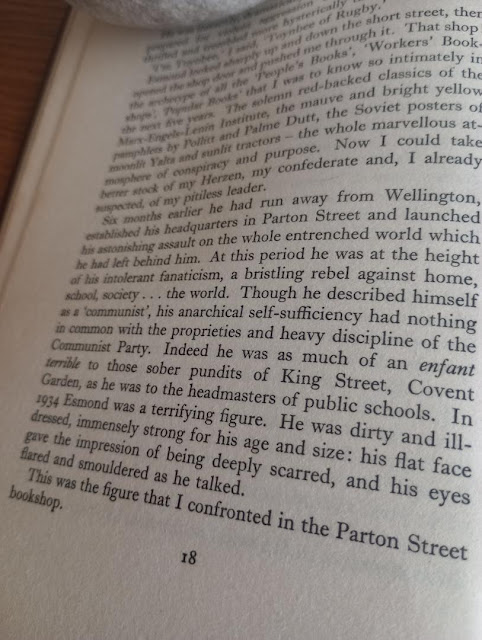

Above is an extract from "Friends Apart" - a description of Esmond Romilly as he appeared when Philip Toynbee first encountered him. Philip, eighteen, ran away from Rugby (his private school) to join Esmond, then fifteen, who had run away from his private school, Wellington. Philip's account is hilarious - vivid, self-deprecating, emotional and entirely without subtext or ulterior motive. (Other than, very subtley, to point out his own inadequacy by comparison.)

Polly, who quotes much of this in her book, manages to transform it into a rather dull and pedestrian account of some boyish leftists who had the very highest leftwing political ideals even though they had been born into upper-middle-class families and had been privately educated.

Her whole book is about being the descendant of upper-middle-class families and the advantages this confers. For every mention of these class antecedents she then has to justify herself by saying that she is and always has been "on the left" and so were her ancestors, and so they are much better than everyone else. This seems to be the message of the book, that being upper-middle-class is to be better than anyone else (why else would she be so careful to keep on emphasising her semi-noble ancestors), and that being on the left is being better than anyone else. Double winner, Polly!

In Polly's book, Esmond features because of being the nephew (some say illegitimate son) of Winston Churchill and was married to the aristocratic Jessica Mitford. Polly makes sure to include the information that Jessica Mitford was Polly's godmother. Jasper doesn't get a look in as he was not aristocratic or related to anyone famous.

Polly is a frightful snob. She is careful to list all her aristocratic ancestors in full detail. The ones who are not aristocratic (who went bankrupt for example - at least two of them) or were otherwise insignificant, are hardly given a paragraph.

I am a few years younger than the author, and used to read the Guardian in the years when she was a womens' page columnist, but didn't take to her. I found her sanctimonious "leftism" and patronising tone boring and soon stopped reading her columns. I did note that her byline photo remained the same for years, always making her look much younger than she was. The photograph beamed out from the Guardian for years and years showed her character in her expression - a smug simper. Here is pretty little Polly - a blonde (not a natural one, as photos from this memoir show), used to charming people and getting her own way.

I've always thought that anyone who still calls themselves Polly in their sixties and seventies is hankering after their lost childhood - and lo and behold, it turns out that she was christened Mary Louisa - but hung on to her pretty childhood nickname throughout her life.

I later found that my longstanding impression that she remained, at heart, a silly, spoilt little girl, has not been altered by reading this memoir. If anything, the memoir has confirmed it.

I thought I would find her trademark smugness and complacency irritating, and so it proved. I almost snapped the book shut and almost flung it aside in the early chapters, so boring was it to keep on reading about how superior it is to be "on the left" even if you have a holiday home in Italy and a multi-million pound house in London. She admits on Twitter (2012) to the holiday home in Italy but denies that it was in Tuscany and says she has it no longer.

In the last chapter of the memoir, however, she admits to having a holiday home in Sussex. So much for her leftist rants in the Guardian about middle-class property owners hoarding property that should be let to the poor. Camels and eyes of needles kept on coming to mind as I read on. She smugly admits to failing her 11-plus, then being rescued by her parents sending her to a private school - not for her the run-down secondary modern. She admits she paid for private school for two of her four children - this is typical leftie "Do as I say, not as I do" behaviour. Harriet Harman, who campaigned via her position as a grandee of the Labour Party for the abolition of Grammar Schools, chose to send her son to one. Because, presumably, she wanted the advantages this would confer for her own child, while denying them to others. Diane Abbott's choice to send her son to the fee-paying top private City of London School is more understandable - being the black son of a black single mother (albeit a member of the Shadow Cabinet) represents a hurdle one would want to overcome if one had the means, ideals or no ideals.

One of the deep failures of logic in this line of thinking is that she assumes everyone would want to be a journalist or a doctor or a lawyer. It is therefore so unfair that these careers are reserved for scions of the upper middle-classes. Well, Polly dear, you are wrong. Not everyone wants to be a journalist, doctor or lawyer. I have met many very happy and fulfilled plumbers, decorators, electricians and carpenters in my lifetime. Conversely I have met several doctors who complain of unbelievable levels of overwork, and lawyers who, while not actually complaining, (they are very well paid, after all), look drained and exhausted and struggle to have any family life. Polly's flawed (and self-centred) logic is that because she has enjoyed her career, everyone else would love to have the same.

I've also met poorly paid journalists, who, while they like their job, don't recommend it any more than they would recommend acting as a career - both represent a chimera of apparent fame, but actually shallow celebrity that is soon forgotten.

I kept going in the hope of reading more about her father Philip, her grandfather Arnold Toynbee, and other famous (in their day) eccentrics. This was what I found reasonably interesting in the book.

These eccentric middle-class and upper middle-class intellectuals remind me of the Knox brothers.

Their relative Penelope Fitzgerald (nee Knox) wrote a superbly witty, detailed and empathetic account of these four (her father and three uncles.) Apart from their intense interest in literature and religion, the extraordinary eccentricity of the four Knox brothers is their most outstanding characteristic. In fact, intensely intelligent people often come across as eccentric, I think. The author captures, in dry, succinct prose, their loveable awkwardness and their fondness for each other in a close-knit family. She relates what are obviously family anecdotes which are sometimes laugh-out-loud funny. The similarity to Philip Toynbee (highly eccentric, highly intelligent, and a superbly witty writer) is notable. Philip Toynbee even became interested in religion later in life, despite his initial communist atheism.

The Knox Brothers is a far more entertaining and informative book than Polly's. That's because Polly can't stop interjecting moral lessons throughout about leftism. Penelope just presents the lovable and endearing old boys as they were, Polly always wants to point out a lesson.

The lesson hammered out over and over is that leftism is right and everyone else is wrong. On many occasions she just states this categorically, without any self-awareness. Everyone else is wrong. She never questions this, never wonders why (in her own words) the Tories have been in power for two-thirds of her lifetime. She infers that it is because the electorate are stupid or believe lies. Or the electoral system is rigged. It never occurs to her that the Tories are elected because a democratic system of one person one vote shows that the larger mass of the British people broadly agree with them.

The overall tone-deaf obsession becomes more and more boring, leavened slightly by the interesting family photographs and vignettes of her elder sister Josephine, and other tragic figures from her family.

I was glad to finish this book, and returned to "Friends Apart" with renewed interest - her father's prose certainly sings, and is laugh-out-loud funny in places. It has no dictatorial moral asides throughout, unlike his daughter's.